Los renos de la isla de St. Matthew

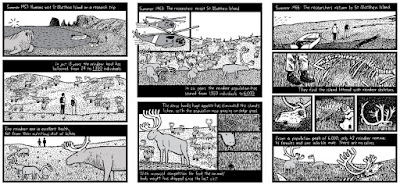

Un caso asombroso de desarrollo y desaparición de una especie introducida artificialmente en una región cerrada que nos hace reflexionar sobre la interdependencia de las especies en un ecosistema y la fragilidad de su dependencia con respecto a las variaciones de su ambiente. A continuación una serie de extractos de varias fuentes que permiten una mirada rápida sobre el tema. Es de destacar el trabajo de ilustración de Stuart Mc Millen sobre temas de ecología y medio ambiente.

Imagen: https://www.stuartmcmillen.com/comic/st-matthew-island/#page-1

Saint Matthew es una apartada isla junto a Alaska que durante siglos había estado tranquila en medio del frío Mar de Bering. Un punto como otro cualquiera en un inmenso desierto azul de agua y hielo al que, durante la segunda guerra mundial, algún cerebro militar se le ocurrió darle una función bélica instalando una estación de radio (Long range radio navigation system, LORAN)

Corría el peligroso año 1944 cuando se designó un equipo de 19 hombres que se encargarían de las instalaciones y del proyecto en la isla. Junto con todos los materiales a bordo, también se cargaron 29 renos que, en caso de necesidades sobrevenidas, pudieran servir de aprovisionamiento y alimento. Estando en guerra, nunca se sabe lo que puede pasar…

Sin embargo, cosas del destino, la historia quiso que la guerra terminara un año más tarde y los planes del alto mando ordenaran desmontar el campamento y volver a casa. Dicho y hecho, aquellos 19 hombres empacaron, embarcaron y regresaron a sus hogares… dejando a aquellos 29 renos en la isla.

Saint Matthew volvía a ser una isla desierta, aunque en esta ocasión albergaba a unos invitados recien llegados que, en ausencia de humanos, se convertirían en amos y señores del lugar.

Los renos se acomodaron a sus anchas y, con un clima adecuado, una vegetación abundante y sobre todo, sin depredadores que les pudieran incordiar, debieron pensar que el ser abandonados en aquella remota isla, al fin y al cabo, no iba a ser tan mala idea.

Pero ya sabéis que el tiempo pasa volando, aunque seas un reno feliz y resulta que en 1957, los curiosos habitantes de Saint Matthew iban a recibir de nuevo a un puñado humanos curioseando por allí.

Se trataba de un equipo de investigadores que al llegar se quedó asombrado… en tan solo un periodo de 13 años la colonia de renos había pasado de los 29 originales a 1350 ejemplares.

Los renos, toda una colonia a estas alturas, estaban bien alimentados, saludables y se habían multiplicado a un ritmo más que considerable.

Desde aquel año de 1957 hasta la próxima visita humana a Saint Matthew habrían de pasar otros 6 años, para situarnos en 1963.

La población de renos en esos seis años había pasado de 1350 renos a la ya multitudinaria cifra de 6.000 ejemplares. Un fascinante crecimiento que dejó con la boca abierta a los investigadores que regresaron a Saint Matthew… aquel asombro se convertiría en estupor tan solo 3 años después…

1966. Nuevos investigadores, interesados en esta interesante colonia de renos regresan a la isla y se encuentran con lo impensable… centenares de huesos, esqueletos y cadáveres diseminados por toda la isla…

En el espectacular lapso de tres años (1963 a 1966) la población de 6.000 renos se había visto reducida drásticamente a cifras escalofriantes: Sólamente habían sobrevivido 42 ejemplares, de los cuáles y para más desgracia, tan sólo quedaba un macho que, posteriormente se comprobó esteril.

La isla, antes verde y fértil, se encontraba totalmente agotada y la vegetación apenas se encontraba cuando antes abundaba por cualquier rincón.

El desmesurado crecimiento de la población acabó con los recursos de Saint Matthew hasta que un breve invierno de escasez, bastó para acabar con la próspera comunidad de renos.

Alaska Science Forum, November 13, 2003When Reindeer Paradise Turned to Purgatory

Article #1672 by Ned RozellThis column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.During World War II, while trying to stock a remote island in the Bering Sea with an emergency food source, the U.S. Coast Guard set in motion a classic experiment in the boom and bust of a wildlife population.The island was St. Matthew, an unoccupied 32-mile long, four-mile wide sliver of tundra and cliffs in the Bering Sea, more than 200 miles from the nearest Alaska village. In 1944, the Coast Guard installed a loran (long range aids to navigation) station on St. Matthew to help captains of U.S. ships and aircraft pilots pinpoint their locations. The Coast Guard stationed 19 men on St. Matthew Island to operate the station. Those men—electrical technicians, cooks, medics, and others—made up the entire human population of the island.In August 1944, the Coast Guard released 29 reindeer on the island as a backup food source for the men. Barged over from Nunivak Island, the animals landed in an ungulate paradise: lichen mats four inches thick carpeted areas of the island, and the men of the Coast Guard station were the reindeer’s only potential predators.The men left before they had the chance to shoot a reindeer. With the end of World War II approaching, the Coast Guard pulled the men from the island. St. Matthew’s remaining residents were the seabirds that nest on its cliffs, McKay’s snow buntings and other ground-nesting birds, arctic foxes, a single species of vole, and 29 reindeer.St. Matthew then had the classic ingredients for a population explosion—a group of healthy large herbivores with a limited food supply and no creature above them in the food chain. That’s what Dave Klein saw when he visited the island in 1957.Klein was then a biologist working for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He is now a professor emeritus with the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Institute of Arctic Biology. The first time he hiked the length of St. Matthew Island in 1957, he and field assistant Jim Whisenhant counted 1,350 reindeer, most of which were fat and in excellent shape. Klein noticed that reindeer had trampled and overgrazed some lichen mats, foreshadowing a disaster to come.Klein did not get a chance to return to the island until the summer of 1963, when a Coast Guard cutter dropped him and three other scientists off on the island. As their boots hit the shore, they saw reindeer tracks, reindeer droppings, bent-over willows, and reindeer after reindeer.“We counted 6,000 of them,” Klein said. “They were really hammering the lichens.”The herd was then at a staggering density of 47 reindeer per square mile. Klein noted the animals’ body size decreased since his last visit, as had the ratio of yearling reindeer to adults. All signs pointed to a crash ahead.Other work commitments and the difficulty of finding a ride to St. Matthew kept Klein from returning until the summer of 1966, but he heard a startling report from men on a Coast Guard cutter who had gone ashore to hunt reindeer in August 1965—the men had seen dozens of bleached reindeer skeletons scattered over the tundra.When Klein returned in the summer of 1966, he, another biologist and a botanist found the island covered with skeletons; they counted only 42 live reindeer, no fawns, 41 females and one male with abnormal antlers that probably wasn’t able to reproduce. During a few months, the reindeer population of St. Matthew had dropped by 99 percent.By piecing together clues found amid the bones, Klein figured that thousands of reindeer starved during the winter following his last visit, when he counted 6,000 animals on the island. Weather records from St. Paul and Nunivak islands for the winter of 1963-1964 showed an extreme winter in both cold and amount of snowfall.With no breeding population, the reindeer of St. Matthew Island died off by the 1980s. The unintended experiment in population dynamics and range ecology ended as it began—with winds howling over the green hills of a remote island in the Bering Sea, a place where arctic foxes are once again the largest mammals roaming the tundra.

*-*

Imagen: https://www.stuartmcmillen.com/comic/st-matthew-island/#page-1

*-*

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario